“Spirit is Life. It flows thru the death of me endlessly like a river unafraid of becoming the sea.” —Gregory Corso

ST. LOUIS — Stretching 2,340 miles, the Mississippi River is a mighty border for eight U.S. states, including Missouri, home to St. Louis. This city, once thriving amid industrial expansion, fell into decline post-midcentury. German artist Anselm Kiefer, an outsider, has recast the Mississippi’s narrative. His exhibition, Anselm Kiefer: Becoming the Sea, at the Saint Louis Art Museum, marks his first major U.S. show in two decades. The exhibit showcases 40 pieces from the past 50 years, with half crafted in the last five. Among them are five massive canvases lining the museum’s 1904 Sculpture Hall. Kiefer’s Romanticism celebrates the Mississippi as a symbol of both industry and creativity, blending nostalgia for his childhood Rhine with the feminine spirits of North American Indigenous cultures and Wagner’s Rhinemaidens. References to poets like Paul Celan and Gregory Corso, who inspired the exhibition’s title, add depth to his narrative.

Anselm Kiefer’s recent works employ a palette of gold and aquamarine, transforming the Mississippi’s muddy hue into a glittering spectacle. A standout piece is “Missouri, Mississippi” (2024), a 30-foot diptych. It features a water nymph entwined with the Missouri River, with “St. Louis” elegantly scripted across her knee. Below, waves crash beneath a saffron sky, inspired by Kiefer’s 1991 visit to the Melvin Price Lock and Dam. The river’s aerial view suggests divine leisure, while the industrial marvels below exude energy. Growing up near these rivers, one can’t view flyover country the same way after experiencing this work.

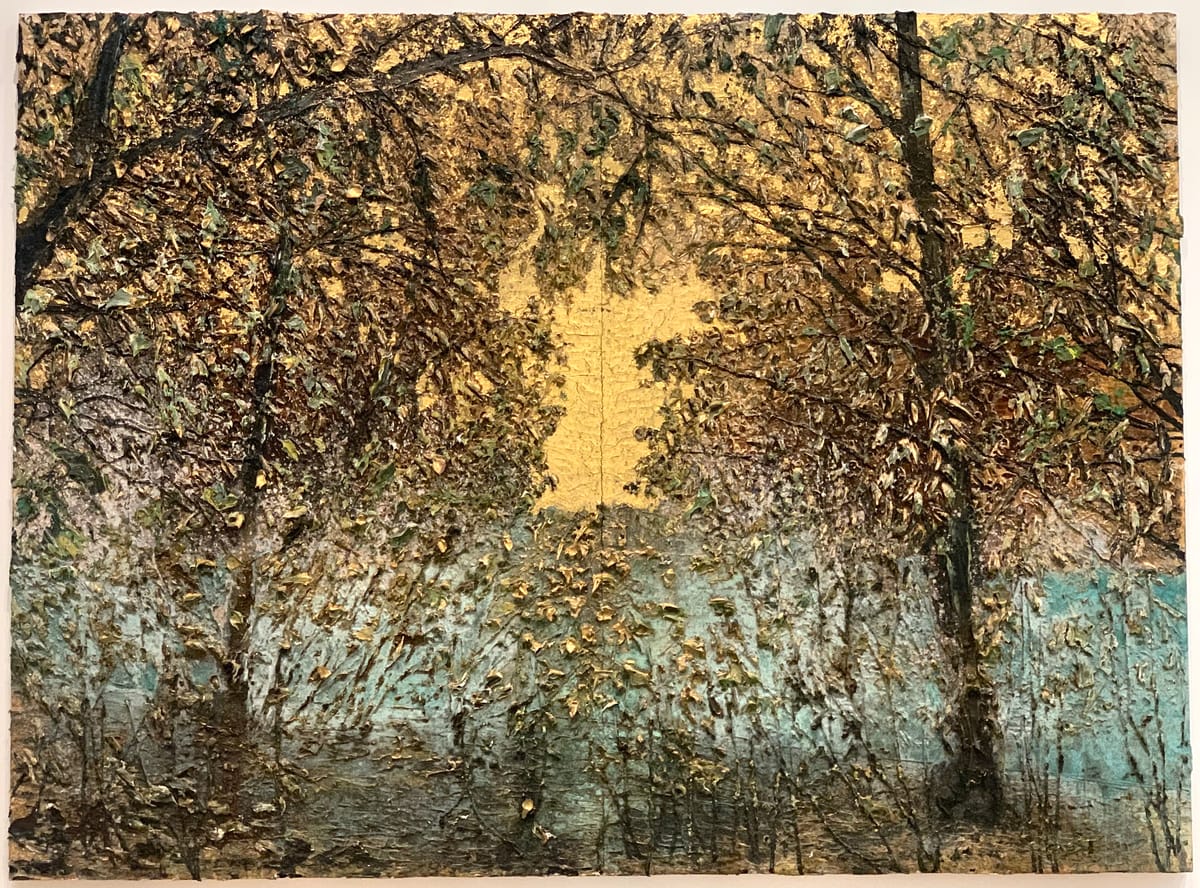

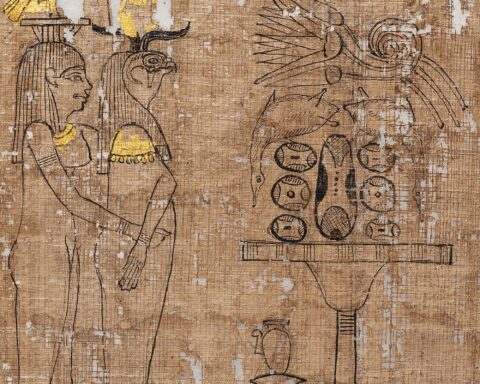

Within the museum’s East Building, Kiefer’s textured green-and-gold pieces create an intimate setting. In “Der Rhine” (The Rhine, 2024), the Black Forest’s branches form a fiery brocade over the river. Opposite is “Dans ce vert linceul” (In This Green Shroud) (2024), featuring a figure in repose, suggesting a unity with nature. The Weil Gallery highlights works from Die Frauen der Antike (The Women of Antiquity) (2018–25), where light plays off representations of female artists and martyrs. Outside, the art resonates with Forest Park’s landscape, echoing the Rustbelt’s weathered charm.

The exhibition’s newer paintings, like “Becoming the Ocean, for Gregory Corso” (2024), contain echoes of Kiefer’s past works, such as “Brennstabe” (Fuel Rods) (1984–87). Though still grand, they feel more suited to the gallery than the towering pieces in the Sculpture Hall, reminiscent of the Cathedral Basilica’s mosaics. While awe-inspiring, some installations seem somewhat repetitive. If Kiefer’s monumental status is literal, the space works. Yet, there’s a longing for a more grounded portrayal of rivers, capturing both majesty and human vulnerability.

Thanks to generous donors, Becoming the Sea is free to the public. Many will revel in its epic scale and beauty. This populist appeal is poignant, especially after a deadly tornado in May devastated St. Louis, felling 5,000 trees in the park. Near the museum, fallen branches serve as a somber reminder of nature’s duality. Whether visitors leave the exhibition less fearful depends on their response to Kiefer’s vision and their broader perspective on art. Perhaps this is my Romantic side speaking.