Editor’s Note: The following article contains content that may be distressing to some readers.

PHILADELPHIA — At the tender age of five, Salvador Dalí committed an alarming act by pushing a friend off a bridge. By 29, he had “trampled” a woman who complimented his feet, and at 30, his obsession with Hitler led to a temporary ousting from the Surrealist movement. A mere five years later, his permanent expulsion was secured after he sent unsettling letters to André Breton, co-founder of the movement, expressing pleasure in reading about the lynchings of Black Americans.

While the Philadelphia Art Museum’s ‘Dreamworld’ exhibit, marking the 100th anniversary of Surrealism, might not be expected to delve into every grim aspect of Dalí’s controversial life, it is concerning that it barely grazes the surface. The exhibition is visually striking, showcasing an impressive range of Surrealist works, both famed and lesser-known. In a time when learning from an antifascist and optimistic movement is crucial, the exhibit fails to sufficiently provide the necessary historical and political context, such as the movement’s birth amid World War I’s horrors, to fully convey its relevance.

Instead, the artworks are categorized vaguely, with wall texts that offer little more than platitudes. The description of Surrealists’ interest in nature, for example, pales in comparison to cultural critic Naomi Klein’s insights. The exhibit states that Surrealists viewed rationalism as alienating, presenting landscapes as imaginative windows. Klein, however, notes their attempts to merge with nature as an escape from deadly progress. This superficial approach renders the exhibit, ironically, somewhat bland.

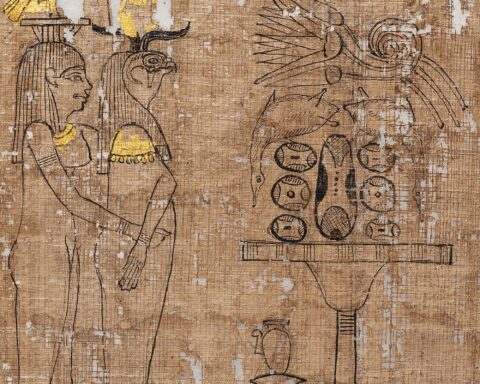

Ignoring the wall texts, a walk through ‘Dreamworld’ feels like traversing a mystical threshold into a collective unconscious. Surreal images abound, from amoeba-like forms to minotaurs by artists like Picasso and Carrington. Noteworthy is the inclusion of works by lesser-known surrealists, including women and artists from regions like Romania and Cuba, who used the movement’s dream space to address war and genocide.

Yet, many artists’ stories remain untold. Who was Rita Kernn-Larsen, a rare female figure in early European Surrealism, and why did she create unsettling works like “The Women’s Uprising”? The lack of context for artists like Suzanne Van Damme and Victor Brauner diminishes understanding of Surrealism’s exploration of the unconscious. The exhibit’s failure to address Dalí’s troubling politics, such as his admiration for Franco, is equally problematic. Understanding the difference between illustrating and combating monsters requires a full narrative, something ‘Dreamworld’ struggles to provide, leaving visitors to seek more information independently.